A YouTube video opens with four Indians immersed in muddied waters, as a voice in the background announces that they’re ready to cross another set of hills with help from a “donker” from Colombia. “The donker will only accompany us till the third hill range…we can give our bags to him for this part of the journey and he’ll charge us $30 or $40,” says Jaspal Sharma, the man behind the voice.

With close to half a million views, this scene describing four Indian migrants’ ordeal eventually meeting the ‘mafia’ in the Panama jungle is only the fourth in a series of videos that Sharma, a self-styled “dunki influencer”, has uploaded. Today, Sharma has received a work permit in California, a far contrast from the hardships shown in his video series uploaded close to a year ago. But the urge to create content is still there.

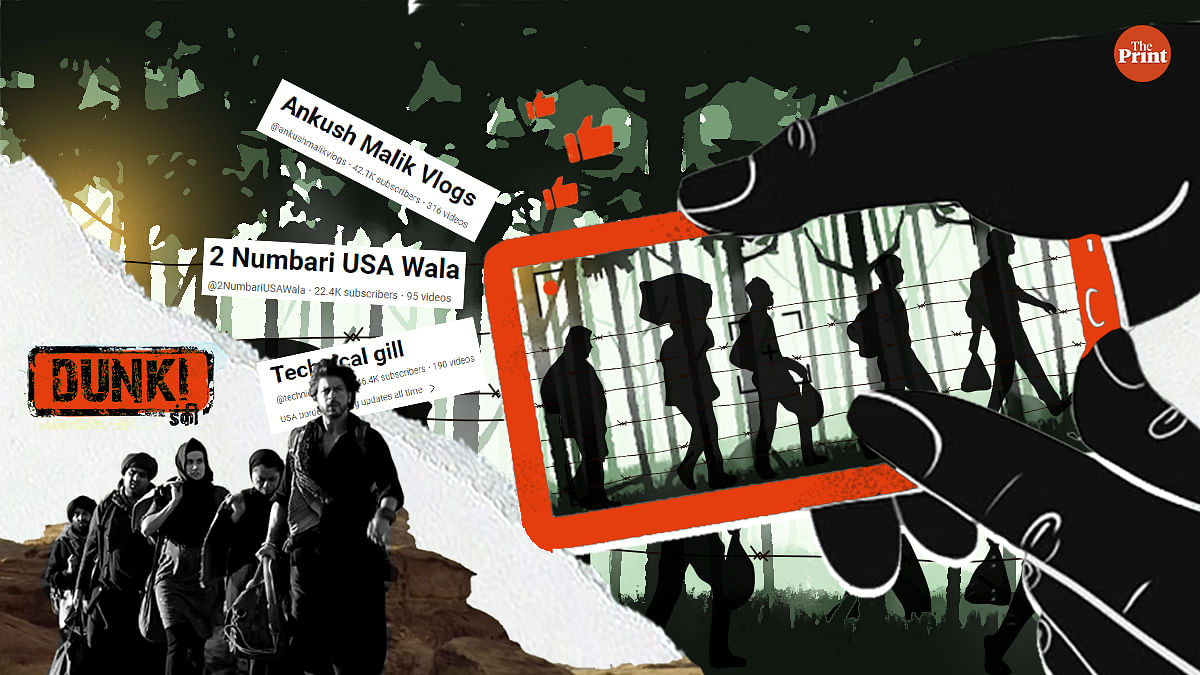

Sharma, who goes by the name of ‘2 Numbari USA Wala’, is only one of the dozens of Indians who are now taking to YouTube, Instagram, and TikTok to document their migration journeys. They offer tips, route suggestions and risk assessments to hop from one country to another, especially the tricky forest between Colombia and Panama and the US-Mexico border. In fact, Indians rank third when it comes to illegal immigration to the US. Hundreds of thousands of agog viewers like, comment and watch them trudge along the dangerous area to succeed.

As the Shah Rukh Khan-starrer Rajkumar Hirani movie now takes the ‘dunki’ phenomenon to a pop-cultural level, the term ‘donkey flight’—hopping from one place to another or taking an informal route for migration—enters common parlance. Unlike legal migration, known as the ‘1 Numbari’ method, ‘2 Numbari’ migrants are taking donkey-flights, a popular method of undocumented immigration.

On social media, the hashtags ‘USAdonkey’, ‘dunki’, and ‘2numbari’ have gained popularity among those discussing or creating content about the subject. It’s the perceived illegality and danger

Documenting the dunki journey

Sharma, 33, first tried to migrate to Australia through the legal route and submitted all his paperwork. “But they required too much documentation and proof of income, so it didn’t work out,” he says. The idea of running a YouTube channel came to him much before he started his dunki journey. Sharma cites the farmers’ protests as an impetus that prompted him to make vlogs.

“I left India in 2022 after the farmers’ protests. My grandfather had close ties with the local BJP members and enjoyed some clout but things changed after we participated in the farmers’ protests,” says the YouTuber, who belongs to the Rajpura region in Punjab but is now working at an Indian store in California. While his wife is no more, the rest of his family still lives in Punjab.

“I was already running a YouTube channel and making content since the time of the farmers’ protests. So, I just thought of taking videos when I left on my journey. Sometimes, there were problems with data or connectivity; I’d film my trip and upload it later when I got (Internet) access,” he says.

Many are aware of the risk of outing themselves on social media, but they see themselves as do-gooders for their communities back home. The influencers say they are confident because legal help from human rights lawyers in the US is easier to access.

It’s Sunday, 24 December, and at 9 pm India Standard Time, the migrant influencer ‘Technical Gill’ goes live for his 34,000+ Instagram followers. Almost 300 viewers were watching the livestream at any point in time. Dozens left comments seeking advice on what routes to take, the best agents to look for, and how much money is required for the journey.

“France da ki khabar aa? (What’s going on in France?),” reads one comment. Many of Gill’s followers wanted to know the recent news of a plane getting apprehended in France, which carried 303 passengers, most of whom were Indians. The flight was originally bound for Nicaragua but was sent back to Mumbai by the French authorities suspecting human trafficking and illegal immigration. It was reported that nearly four dozen passengers on the plane had filed asylum applications.

Such live streams are held every week, often addressing people’s concerns about immigration. Many ask about the risks involved in the ‘2 Numbari’ route, advice on moving to Canada, and other related queries.

Gill, who prefers to only disclose his surname, has about 46,000 subscribers on YouTube with close to 17 million channel views. He frequently shares video content showing border crossings, arrests on the US-Mexico border, and other risks encountered on the route from South America (particularly Panama) to the US.

He says he chose to settle in Mexico in 2016 after first trying to get a job in Birmingham in the UK. The influencer, who is now well-versed in Spanish and has “all legal documentation”, says he took to social media to “help my Indian brothers”.

Another popular figure is Ankush Malik from Israna village in Haryana. With 41,900 subscribers and close to seven million channel viewers on YouTube, along with over 56,000 followers on Instagram, Malik uploads videos that depict the nitty-gritty of undocumented immigration. From a 15-part series showing his journey from India to the US to his more recent vlogs celebrating the receipt of his work permit or trips to the gas station, Malik weaves in a colourful story of achieving the ‘American Dream’.

On Instagram, one of his most recent reels is an insouciant jibe at those who deride immigrants like him. “Kuch nahi raha in baatan ka,” he says in a sarcastic tone, referring to those who stress upon studying, getting a degree, and going abroad as white-collar workers. The video ends with him making a mock gunshot sound and a quip that he’s already sitting in America despite not heeding that advice.

“I can’t speak for others, but seeing Ankush bhai’s videos definitely influenced me. He’s very popular here. All of Haryana’s youths are leaving the state as it is,” says Amit Deswal, a ‘2 Numbari’ migrant from Panipat, who follows Malik.

Deswal took his ‘dunki’ in 2022, and has now managed to gain asylum and work in California. “I took a flight to Mexico via the UK and crossed the Mexico border into the US. We were kept in a detention centre but they treated us well and just a day or two later, we were released. My appeal is pending before the immigration courts but until then I have been allowed to work,” he says.

Money matters and risk factors

For many like Deswal, the American immigration system feels like a matter of ‘kismat’ or destiny. And migration influencers like Malik and Sharma are helping shape that aspiration, raking in channel views and subscribers along this path. Deswal also says that there’s money to be made in this risky line of work.

“The main purpose of those who run YouTube channels is money. I am also very famous on Instagram, I’m popular among all the Haryanvis here in the US because of my dunki. But successfully running a YouTube channel is a way to earn money, they have subscribers and it takes time. Once you make it to the US and manage to get a work permit, who has the time to make videos? Only if you’re earning revenue will you make content,” he adds.

While some are now reaping profits, the fear and stigma of illegality still looms large on many. Krishan Khatkar, a newly minted YouTuber who made his journey across the Panama forest and treacherous Darién Gap this year, declined to comment about his decision to start a YouTube channel.

“Ultimately, we haven’t migrated legally, why would anyone threaten their migration by talking about it,” he says.

Despite Khatkar citing risks as a reason not to comment, many others continue to curiously film their entire journeys, even if it poses a risk to their asylum process.

“Often, behind those videos is a donker who is influencing them. Migrants are deprived of resources, food and water and these are treacherous journeys in difficult climates. So, there is pressure to act as per the instructions of the donker, who may be pressuring them into making these videos,” says Pari Saikia, an award-winning journalist who reports on human trafficking. Saikia also points out that taking money as a commission and getting videos made to recommend a particular donker or agent is fairly common.

Gill echoes these concerns. “A lot of Indians come through agents who then take them for a ride. Many times, I get messages on Instagram and YouTube from someone who is stuck in a third country, they have been abandoned by their agents who fleeced them of their money. So, I try to help them with YouTube videos, especially because I have lived and worked in Mexico and other countries so I know the system,” he says.

Almost everyone who takes a donkey flight relies on ‘agents,’ searching for a reliable and affordable option. Some agents get the job done for Rs 35-40 lakh, while some charge Rs 50 lakh or upwards. The cost of securing an agent’s help depends on the chosen route. Most influencers agree that crossing into the US via the Panama forest and the risky trail of the Darien Gap is much cheaper compared to other options, such as crossing the border from Mexico after arriving there by a flight from Europe.

But whatever the risks and costs of the journey, illegal immigration is rampant. And migration influencers are here to stay.

Data from the Pew Research Center reveals that Indians form the third-highest number of illegal immigrants to the US. According to the US Customs & Border Protection (UCBP), between October 2022 and September 2023, at least 96,917 Indians were apprehended, expelled, or denied entry due to lack of documentation. Reports highlight an astonishing fivefold increase from the same period in 2019-2020, when the number was just 19,883.

From the increase in immigration since the pandemic, change in government policies under Joe Biden from what they were during the Donald Trump administration, the marginalisation of minorities and dissenters in Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s India, and the adoption of newer and more sophisticated methods by agents and traffickers, many factors are said to have contributed to the rise of desperation among Indians to migrate.

Migration scholar Sugandha Nagpal also notes the surge in Indian migrants becoming social media influencers by showcasing their illegal migration journeys and depicting life after legal migration.

According to Nagpal, these videos are posted to provide information to aspirational migrants, aiding their decision-making. “While videos normalising illegal migration can be seen as risky, they can only be combated with increasing information flow. It places the onus on the Indian government and institutions concerned with regularising migration to reach out to young Indians through social media platforms where they can disseminate information on destination countries, immigration requirements, and post-migration challenges,” she says.

Unfazed by criticism

Not everyone is a fan of dunki influencers. Many say they are setting a bad example.

“Congratulations for making genuine travellers like us difficult to get a US tourist visa (sic),” one user commented on Malik’s video. “Thx bro due to people like you, Indians face a hard time getting visa,” wrote another.

Despite his popularity, Gill says he shares these concerns and spreads awareness about the problems of dunki migration on his channels. “I don’t make videos promoting the idea of dunki but to help people avoid its risks. If someone comes from Punjab and gets stuck in their route, I try to help them out,” he says.

Gill’s videos also tell cautionary tales. One such video, titled ‘Mafia uses girls Panama jungle…USA Donkey not safe girls’ warns young women to avoid taking the path to the US through the Panama jungle. Having experienced the journey himself, Gill says he doesn’t want others to make the same mistakes.

His most viewed videos have garnered over one million views. Titled ‘Mexico border crossing to USA’, one video shows a group of people being hugged and greeted by another group after crossing a barbed wire fence in a densely leafy area. YouTubers from across the globe criticised the border-crossing in the comments.

“Yes! Show them a video of what it’s like to get detained and deported for illegally crossing the US border! Especially if you have been here long enough to find a job and buy a house. No excuses, deported. Period.” Others write things like “Don’t migrate….make your country great.”

However, even as they receive both praise and hate, this new crop of migration influencers remains unfazed. Sharma concedes that though many people question the methods, the general response has remained promising. “Some people say, ‘You (dunki-takers) are spending Rs 50 lakh on agents and to take such trips, just to end up as a daily wage-worker in the US. Why not use such money to get a good job in India instead?’ But tell me, even if I got the best job here, would I earn as much?” he asks.

Sharma claims that he earned Rs 3 lakh a month as a working-class person in the US. “In India, even the best of jobs would pay me no more than Rs 2 lakh a month. And the quality of life (in the US) is far better,” Sharma adds.

A big chunk of viewers continues to tune in from Pakistan, Nepal, Dubai, and even Saudi Arabia to watch the dunki influencers.

“For all the negativity about our illegal methods, there is also someone writing in to say we bring them hope. Many are dreaming of a better life, and we show how it could be,” says Sharma.